Will we know extraterrestrial life when we see it?

In a 1967 episode of Star Trek, Captain Kirk and crew investigated the mysterious murders of miners on the planet Janus VI. The killer, it turned out, was a rock monster called the Horta. But the Enterprise’s sensors hadn’t registered any signs of life in the creature. The Horta was a silicon-based life-form, rather than carbon-based like living things on Earth.

Still, it didn’t take long to determine that the Horta was alive. The first clue was that it skittered about. Spock closed the case with a mind meld, learning that the creature was the last of its kind, protecting its throng of eggs.

But recognizing life on different worlds isn’t likely to be this simple, especially if the recipe for life elsewhere doesn’t use familiar ingredients. There may even be things alive on Earth that have been overlooked because they don’t fit standard definitions of life, some scientists suspect. Astrobiologists need some ground rules — with some built-in wiggle room — for when they can confidently declare, “It’s alive!”

Among the researchers working out those rules is theoretical physicist Christoph Adami, who watches his own version of silicon-based life grow inside a computer at Michigan State University in East Lansing.

“It’s easy when it’s easy,” Adami says. “If you find something walking around and waving at you, it won’t be that hard to figure out that you’ve found life.” But chances are, the first aliens that humans encounter won’t be little green men. They will probably be tiny microbes of one color or another — or perhaps no color at all.

By definition

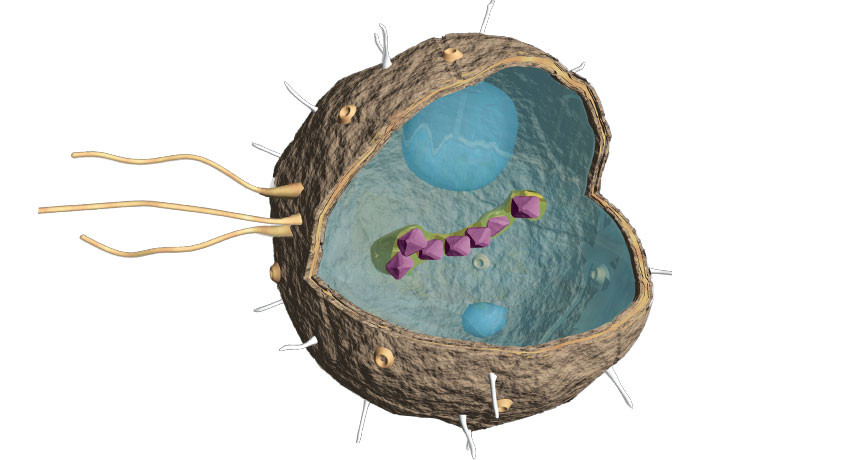

Trying to figure out how to recognize those alien microbes, especially if they are very strange, has led scientists to propose some basic criteria for distinguishing living from nonliving things. Many researchers insist that features such as active metabolism, reproduction and Darwinian evolution are de rigueur for any life, including extraterrestrials. Others add the requirement that life must have cells big enough to contain protein-building machines called ribosomes.

But such definitions can be overly restrictive. A list of specific criteria for life may give scientists tunnel vision, blinding them to the diversity of living things in the universe, especially in extreme environments, says philosopher of science Carol Cleland of the University of Colorado Boulder. Narrow definitions will “act as blinkers if you run into a form of life that’s very different.”

Some scientists, for instance, say viruses aren’t alive because they rely on their host cells to reproduce. But Adami disagrees. “There’s no doubt in my mind that biochemical viruses are alive,” he says. “They don’t carry with them everything they need to survive, but neither do we.” What’s important, Adami says, is that viruses transmit genetic information from one generation to another. Life, he says, is information that replicates.

Darwinian evolution should be off the table, too, Cleland says. Humans probably won’t be able to tell at a quick glance whether something is evolving, anyway. “Evolvability is hard to detect,” she says, “because you’ve got a snapshot and you don’t have time to hang around and watch it evolve.”

Cell size restrictions may also squeeze minuscule microbes out of consideration as aliens. But a cell too tiny to contain ribosomes may still be big enough if it uses RNA instead of proteins to carry out biochemical reactions, says Steven Benner, an astrobiologist at the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Alachua, Fla. Cells are thought necessary because they separate one organism from another. But layers of clay could provide the needed separation, Adami suggests. Cleland postulates that life could even exist as networks of chemical reactions that don’t require separation at all.

Such fantastical thinking can loosen the grip of rigid criteria limiting scientists’ ability to recognize alien life when they see it. But they will still need to figure out where to look.

Up close and personal

With the discovery in recent years of more than a thousand exoplanets far beyond the solar system, the odds favoring the existence of extraterrestrial life in the cosmos are better than ever. But even the most powerful telescopes can’t detect microscopic organisms directly. Chances of finding microbial life are much higher if scientists can reach out and touch it, which means looking within our solar system, says mineralogist Robert Hazen, of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C.

“You really need a rover down on its hands and knees analyzing chemicals,” Hazen says. Rovers are sampling rocks on Mars (SN: 5/2/15, p. 24) and the Cassini probe has bathed in geysers spewing from Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus (SN: 10/17/15, p. 8). Those mechanical explorers and others in the works may send back signs of life.

But those signs are probably going to be subtle, indirect “biomarkers.” It may be surprisingly difficult to tell whether those biomarkers are from animals, vegetables, microbes or minerals, especially at a distance.

“We really need to have life be as obvious as possible,” says astrobiologist Victoria Meadows, who heads the NASA Astrobiology Institute’s Virtual Planetary Laboratory at the University of Washington in Seattle. By obvious, she partly means Earth-like and partly means that no chemical or geologic process could have produced a similar signature.

Some scientists say life is an “I’ll know it when I see it” phenomenon, says Kathie Thomas-Keprta, a planetary geologist. But life may also be in the eye of the beholder, as Thomas-Keprta knows all too well from studying a Martian meteorite. She was part of a team at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston that studied a meteorite designated ALH84001 (discovered in Antarctica’s Allan Hills ice field in 1984).

In 1996, a team led by Thomas-Keprta’s late colleague David McKay claimed that carbonate globules embedded in the meteorite resembled microscopic life on Earth. The researchers found large organic molecules with the carbonate, indicating that they formed at the same time. Thomas-Keprta also identified tiny magnetite crystals overlapping the globules that closely resemble crystals formed by “magnetotactic” bacteria on Earth. Such bacteria use chains of the crystals as a compass to guide them as they swim in search of nutrients. The researchers believed that they were looking at fossils of ancient Martians.

Other researchers disagreed. The globules and crystals could have formed by chemical or geologic processes, not biology, critics said. Since then, the claim of fossilized Martian life has been widely dismissed.

Surely, recognizing something that is still alive, rather than dead and turned to rock, would be much simpler. But don’t bet on it, Cleland says. There may even be strange forms of life on Earth — a shadow biosphere — that people have overlooked.

Desert varnish

One bit of evidence for shadow terrestrials is “desert varnish,” the dark stains on the sunny sides of rocks in arid areas. Odd, communal life-forms could be sucking energy from the rocks and building the varnish’s hard outer crust, Cleland suggests. Some scientists, for instance, think manganese-oxidizing bacteria or fungi might be responsible for concentrating iron and manganese oxides to create the stains. Unknown microbes may cement the metals with clay and silicate particles to produce the varnish’s shellac. Scientists have tried and failed to re-create desert varnish in the lab using fungi and bacteria.

Critics say that varnishes form too slowly — over thousands of years — to be a microbial process and that oxidizing manganese doesn’t generate enough energy to live on. Desert varnish is most likely a product of physical chemistry, they say.

But that criticism shows bias, Cleland responds. “We have an assumption that life on Earth has a pace,” she says. Shadow life may grow far more leisurely, making it hard for scientists to classify it as alive.

One way to determine whether the varnish has a biological or geologic origin is to measure isotope ratios, Cleland says. Isotopes are forms of elements with differing numbers of neutrons in the nuclei of their atoms. Lighter isotopes, with fewer neutrons, are favored by some biochemical reactions.

“Life is lazy,” says Cleland. “It doesn’t want to haul around an extra neutron.” Concentrations of lighter isotopes could signal the handiwork of living organisms, she notes.

Mineral distortions

To find life, and classify it correctly, look for the odd thing out, suggests Hazen, who is looking for messages in minerals. Minerals on Earth are unevenly distributed, he and colleagues have determined. There are 4,933 recognized minerals on the planet. Hazen and colleagues mapped the locations of 4,831 of them and found that 22 percent exist in only one location (SN Online: 12/8/14). Close to 12 percent occur in only two places, the researchers reported last year in The Canadian Mineralogist.

One reason for the skewed distribution is that evolving life has used local resources and concentrated them into new minerals. Take for example hazenite, named for Hazen. The phosphate mineral is produced only by microbes living in California’s Mono Lake. Actions of other species in other places on Earth have combined with the planet’s geology to make Earth’s mineralogy unique, Hazen wrote with colleagues last year in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

Finding similarly distorted distributions of minerals on other planets or moons could indicate that life exists, or once existed, there. Hazen has advised NASA on how rovers might identify mineral clues to life on Mars.

But determining whether something is unusual might not be as easy as it sounds. Scientists don’t yet know enough about the environment of Mars, Benner says. “Every rover has given us surprises.” He’d like to see a manned fact-finding mission, which he says might lead to a better understanding of the Red Planet and speed up the search for life there.

Mars was once wet (SN Online: 10/8/15) and still has occasional running water (SN: 10/31/15, p. 17). That and other mounting evidence that the Red Planet was once capable of supporting life led Benner to hypothesize in 2013 that Mars may have seeded life on Earth. Whether that hypothesis holds may depend on finding Martians, but Benner doesn’t seem worried.

“I think I would be surprised now if they don’t find life on Mars,” he says. Once the announcement is made, researchers will begin fighting over whether the Martians are real, he predicts. “It will be a good-natured fight because everybody wants to find life, but everybody is aware of the pitfalls of experiments conducted at a 100-million-mile distance by robots.”

Manned missions could easily reach Mars to confirm a find, says Dirk Schulze-Makuch, an astrobiologist at Washington State University in Pullman. “If you have a human with a microscope and the microbe is wiggling and waving back, that’s really hard to refute,” he jokes.

But humans and even probes may have a harder time spotting life on more distant or exotic locales, such as the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. Europa, Enceladus and Titan are frigid places barely kissed by the sun’s energetic rays, but that doesn’t mean they are devoid of life, Schulze-Makuch says. ET hunters are particularly attracted to Europa and Enceladus because liquid oceans slosh beneath their icy crusts. Liquid water is thought to be necessary for many of the chemical reactions that could support life, so it’s one of the primary things astronomers look for.

Going for the less obvious

But water is actually a terrible solvent for forming complex molecules on which life could be based, Schulze-Makuch says. Instead, he thinks, really alien aliens might have spawned at hot spots deep in the hydrocarbon lakes of Saturn’s biggest moon, Titan. There, “you could make something very intriguing. Whether you can get all the way to life, we don’t know,” he says. If he sent a probe to that moon, he would first look for large macro-molecules similar to the DNA, RNA and proteins that Earth life uses, but with a Titanic twist.

He has been studying a natural asphalt lake in Trinidad to learn more about what life in Titan’s lakes might be like. Last July in the journal Life, he and colleagues laid out the physical, chemical and physiological limits that life on Titan would bump up against.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for Titanic life is the extreme cold, says chemical engineer Paulette Clancy of Cornell University. Frosty Titan is so cold that methane — a gas on balmy Earth — is a viscous, almost-freezing liquid, and water “would be like a rock,” she says. Under those conditions, organisms with Earth-like chemistry wouldn’t stand a chance.

For one thing, the membranes that hold in a cell’s guts on Earth wouldn’t work on Titan. Membranes are made of twin sheets of chainlike molecules each with an oxygen-containing head and a long tail of fatty acids. “On Titan,” says Clancy, “long chains would be a disadvantage because they would be frozen in place,” making membranes brittle. Plus, Titan has no free oxygen to form the molecules’ traditional heads.

But Clancy and her Cornell colleagues, chemical engineer James Stevenson and astronomer Jonathan Lunine, simulated experiments under Titan-like conditions. (Molecules that would be stable on Titan would fall apart on Earth, so the researchers had to do computer experiments instead of synthesizing the molecules in a lab.) Short-tailed acrylonitrile molecules with nitrogen-containing heads could spontaneously create stable bubbles called azotosomes, the researchers reported last year in Science Advances. The bubbles are similar to cell membranes.

“Azo” is a prefix that denotes a particular configuration of nitrogen atoms in a molecule. It’s also Greek for “without life.” The word’s meaning “would be ironic if life on Titan were based … on nitrogen,” Clancy says.

Like desert varnish, life on Titan may have unfamiliar pacing that could prevent Earthlings from determining whether azotosomes or other membranous bubbles found in that moon’s methane oceans actually harbor life. With little solar radiation to stimulate evolution and frigid temperatures to slow chemical reactions, life on Titan may be really poky, Schulze-Makuch says. He imagines that Titanic life-spans may stretch to millions of years, with organisms reproducing or even breathing only once every thousand years. Scientists may need to measure metabolic reactions instead of generation times to determine whether something is living on Saturn’s frigid satellite.

Clancy hopes to explore what types of metabolism Titan’s chemistry might allow. Neptune’s icy moon Triton, which is covered in a thin veneer of nitrogen and methane and has nitrogen-spewing geysers, may also be a candidate for new and exciting biochemistry, she says.

With so many options out there, Clancy predicts that there are several planets or moons with life on them. “That we have the lock on the way life decided to develop, I think, is unlikely.”

Many other researchers are also optimistic that life is out there to find. “I think life is a cosmic imperative,” Hazen says. Someday, astrobiologists may come face-to-face with ET. Maybe they will even recognize it when they see it.